苦艾酒(英語:Absinthe

18世紀後期,苦艾酒興起於瑞士納沙泰爾州(Neuchâtel)。在19世紀末和20世紀初,它成為法國大受歡迎的酒精飲料,尤其是在巴黎的藝術家和作家之間。由於其與波希米亞文化之間的因緣,苦艾酒受到社會保守主義者和禁酒主義者的反對。歐內斯特·海明威(Ernest Hemingway)、夏爾·皮埃爾·波德萊爾(Charles Pierre Baudelaire)、保羅·魏爾倫(Paul Verlaine)、阿蒂爾·蘭波(Arthur Rimbaud)、亨利·德·土魯斯-洛特雷克(Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec)、阿梅代奧·莫迪利亞尼(Amedeo Modigliani)、文森特·梵谷(Vincent van Gogh)、奧斯卡·王爾德(Oscar Wilde)、阿萊斯特·克勞利(Aleister Crowley)以及阿爾弗雷德·雅里(Alfred Jarry)都是知名的苦艾酒的擁躉。[6]

苦艾酒也經常被描繪成一個危險的容易上癮的精神藥物[7]。苦艾酒中含有的微量化合物側柏酮(thujone),被指含有毒副作用。到1915年在美國和歐洲大部分國家,包括法國,荷蘭,比利時,瑞士和奧匈帝國,苦艾酒都被取締。雖然苦艾酒受到詆毀,人們卻一直無法證明苦艾酒比普通白酒危險程度更大。撇開酒精本身的作用不說,苦艾酒對人造成的精神影響被誇大了[7]。20世紀90年代,近代的歐盟食品和飲料相關法律取消了針對苦艾酒生產和銷售長期存在的限制,苦艾酒開始復興。由21世紀初,在十幾個國家中崛起了近200個苦艾酒品牌,其中最引人注目的是瑞士,美國,西班牙,法國和捷克共和國的品牌。

詞源

苦艾酒英文為Absinthe,其實是一個法語單詞,在法語中一般指酒精飲料,偶爾也可以指艾草植物,包括稱為大苦艾(grande absinthe)的中亞苦蒿(Artemisia absinthium),和小苦艾(petite absinthe)的西北蒿(Artemisia pontica)。其拉丁名artemisia來自古希臘的狩獵女神阿爾忒彌斯(Artemis)。單詞Absinthe來自拉丁語Absinthium,而Absinthium又是希臘語ἀψίνθιον(apsínthion)拉丁化而成的,它們的本義都是「艾草」(wormwood)[8]。將苦艾用於飲料可以從盧克萊修(Lucretius)的著作《物性論》(De Rerum Natura(I 936-950 ))中得到引證,盧克萊修表示,含有艾草(wormwood)的飲料可以作為作為兒童的藥飲,伴著蜂蜜喝使其容易飲用。使用了詩歌的形式,將這個複雜的理念用比喻的方式講述了出來[9]。有些人聲稱,ἀψίνθιον這個詞在希臘語中的意思是「不能飲用」,但它可解析為波斯詞根spand或aspand,或其變體esfand,意思是駱駝蓬(Peganum Harmala),也被稱為敘利亞芸香(Syrian Rue),但它實際上不是芸香(另一種著名的苦味的草藥)的品種。是否這個詞是從波斯語引入到希臘,或兩者從共同的語源進化而來,目前還不清楚[10]。

absinthe的變體包括absinth,absynthe,和absenta。在歐洲中部和東部生產苦艾酒的地區,Absinth(不包括結尾的e)是最常見的拼寫變異,並特指波西米亞風格的苦艾酒[11]。

不像蘇格蘭威士忌,白蘭地,金酒在 全球範圍內都規範並定義了製作方法和原料,大多數國家都沒有苦艾酒的法律定義。因此,生產者可以任意的在他們的產品上標上「苦艾酒」 ("absinthe" 或"absinth")的標籤,而不受任何法規限制,也沒有標準評判其質量。 合法的苦艾酒生產者遵循歷史上流傳的兩個製造流程中的一個:蒸餾法(distillation)或低溫混合法(cold mixing)。在那些有法規定義苦艾酒的國家(比如瑞士),只允許通過蒸餾生產苦艾酒[57]。

Absinthe: A literary muse

Jane Ciabattari investigates how the powerful spirit that drove Vincent Van Gogh to cut off his ear also inspired great authors from Arthur Rimbaud to Ernest Hemingway.

9 January 2014

Absinthe: How the Green Fairy became literature’s drink

HIDE CAPTION

- The green stuff

- Absinthe, a green liquor with ten times the alcohol content of wine and popular with legendary authors and artists, was banned for most of the past century. (Goran Heckler/Alamy)

Absinthe has inspired many great authors of the last 150 years – and

may have ruined some as well. Jane Ciabattari investigates the green

spirit’s peculiar power.

Arthur Rimbaud called absinthe the “sagebrush of the glaciers” because a key ingredient, the bitter-tasting herb Artemisia absinthium or

wormwood, is plentiful in the icy Val-de-Travers region of Switzerland.

That is where the legendary aromatic drink that came to symbolise

decadence was invented in the late 18th Century. It’s hard to overstate

absinthe’s cultural impact – or imagine a contemporary equivalent.

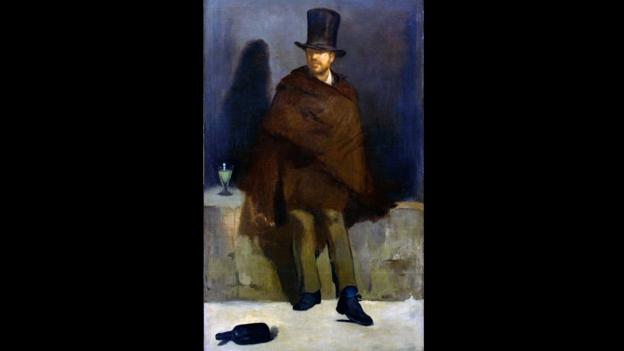

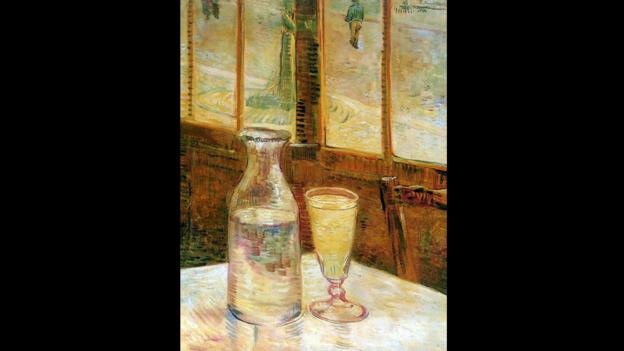

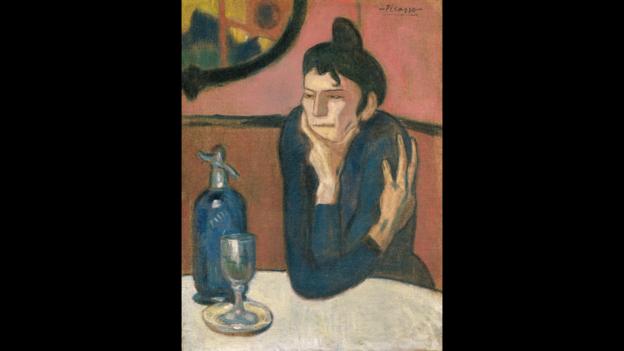

The spirit was a muse extraordinaire from 1859, when Édouard Manet’s The Absinthe Drinker shocked the annual Salon de Paris, to 1914, when Pablo Picasso created his painted bronze sculpture, The Glass of Absinthe. During the Belle Époque, the Green Fairy – nicknamed after its distinctive colour – was the drink of choice for so many writers and artists in Paris that five o’clock was known as the Green Hour, a happy hour when cafes filled with drinkers sitting with glasses of the verdant liquor. Absinthe solidified or destroyed friendships, and created visions and dream-like states that filtered into artistic work. It shaped Symbolism, Surrealism, Modernism, Impressionism, Post-Impressionism and Cubism. Dozens of artists took as their subjects absinthe drinkers and the ritual paraphernalia: a glass, slotted spoon, sugar cubes – sugar softened the bitter bite of cheaper brands – and fountains dripping cold water to dilute the liquor.

Absinthe was, at its conception, not unlike other medicinal herbal preparations (vermouth, the German word for wormwood, among them). Its licorice flavor derived from fennel and anise. But this was an aperitif capable of creating blackouts, pass-outs, hallucinations and bizarre behavior, with nearly ten times the alcohol content of wine. Contemporary analysis indicates that the chemical thujone in wormwood was present in such minute quantities in properly distilled absinthe as to cause little psychoactive effect. It’s more likely that the damage was done by severe alcohol poisoning from drinking twelve to twenty shots a day. Still, the mystique remains.

Muse in a bottle

Rimbaud, Baudelaire, Paul Verlaine, Emile Zola, Alfred Jarry and Oscar Wilde were among scores of writers who were notorious absinthe drinkers. Jarry insisted on drinking his absinthe straight; Baudelaire also used laudanum and opium; Rimbaud combined it with hashish. They wrote of its addictive appeal and effect on the creative process, and set their work in an absinthe-saturated milieu.

In the poem Poison, from his 1857 volume The Flowers of Evil, Baudelaire ranked absinthe ahead of wine and opium: “None of which equals the poison welling up in your eyes that show me my poor soul reversed, my dreams throng to drink at those green distorting pools."

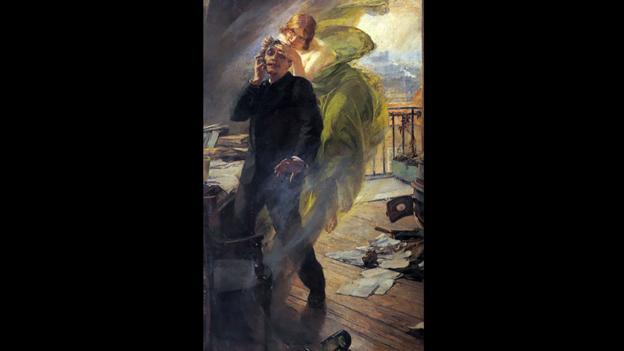

Rimbaud, who “saw poetry as alchemical, a way of changing reality” Edmund White notes in his biography of the poet, saw absinthe as an artistic tool. Rimbaud’s manifesto was unambiguous: he declared that a poet “makes himself a seer through a long, prodigious and rational disordering of all the senses.” Absinthe, with its hallucinogenic effects, could achieve just that.

Guy de Maupassant imbibed, as did characters in many of his short stories. His A Queer Night in Paris features a provincial notary who wangles an invitation to a party in the studio of an acclaimed painter. He drinks so much absinthe he tries to waltz with his chair and then falls to the ground. From that moment he forgets everything, and wakes up naked in a strange bed.

Contemporaries cited absinthe as shortening the lives of Baudelaire, Jarry and poets Verlaine and Alfred de Musset, among others. It may even have precipitated Vincent Van Gogh cutting off his ear. Blamed for causing psychosis, even murder, by 1915 absinthe was banned in France, Switzerland, the US and most of Europe.

Cultural hangover

The Green Fairy faded as a cultural influence for most of the 20th Century, to be replaced by cocktails, martinis and, in the 1960s, a panoply of mind-altering drugs. There were occasional echoes of its power, though mostly nostalgic.

Ernest Hemingway sipped the Green Fairy in Spain in the 1920s as a journalist, and later during the Spanish Civil War. His character Jake Barnes consoles himself with absinthe after Lady Brett runs off with the bullfighter in The Sun Also Rises. In For Whom the Bell Tolls, Robert Jordan brings along a canteen of the stuff. In Death in the Afternoon Hemingway explains he stopped bullfighting because he couldn’t do it happily “except after drinking three or four absinthes, which, while they inflamed my courage, slightly distorted my reflexes."

Hemingway even invented a Death in the Afternoon cocktail for a 1935 celebrity drinks book: “Pour one jigger absinthe into a Champagne glass. Add iced Champagne until it attains the proper opalescent milkiness. Drink three to five of these slowly."

In the late 20th Century, absinthe became a decadent reference point among a new generation of writers based in latter-day Bohemian outposts like San Francisco and New Orleans.

"The absinthe cauterized my throat with its flavor, part pepper, part licorice, part rot,” wrote precocious New Orleans horror writer Poppy Z Brite in a 1989 story, His Mouth Will Taste of Wormwood. The narrator and his boyfriend, jaded grave robbers, have found more than fifty bottles of the now-outlawed liquor, sealed up in a New Orleans family tomb. By the end, the narrator is fantasising about his first bitter kiss of the spirit from beyond the grave.

Still seeing green

Today’s absinthe is a “tongue-numbing drink” that “sharpens the senses,” says Lance Winters, master distiller and proprietor at St George Spirits, which offered the first legal absinthe in the US in late 2007.

“To my mind, absinthe imparts an air of the mystic, a touch of the supernatural – qualities I like in a drink now and again,” says Rosie Schaap, drinks columnist for The New York Times. She recommends “deploying the stuff with a light hand.” Her contemporary absinthe cocktails include the Fascinator – two parts gin, one part dry vermouth, two dashes of absinthe and one mint leaf.

In today’s literary circles, absinthe is more an amusement than a muse – showing up as a hipster cocktail at themed book-launch parties. Now widely available, in versions from the recently-made to the $10,000 a bottle vintage Pernod Fils, the drink seems just another popular culture reference, showing up in a Mad Men episode, as a Marilyn Manson-endorsed signature brand, Mansinthe, and inspiring innumerable drinks recipes, many of which use absinthe as a rinse, not a serious ingredient. You can even buy absinthe dilution apps for your smartphone.

Like the splash added to a cocktail, a literary reference to absinthe today adds a whiff of atmosphere, a reminder of the provocative and form-fracturing writers of the Belle Époque – and that a spirit can indeed inspire.

The spirit was a muse extraordinaire from 1859, when Édouard Manet’s The Absinthe Drinker shocked the annual Salon de Paris, to 1914, when Pablo Picasso created his painted bronze sculpture, The Glass of Absinthe. During the Belle Époque, the Green Fairy – nicknamed after its distinctive colour – was the drink of choice for so many writers and artists in Paris that five o’clock was known as the Green Hour, a happy hour when cafes filled with drinkers sitting with glasses of the verdant liquor. Absinthe solidified or destroyed friendships, and created visions and dream-like states that filtered into artistic work. It shaped Symbolism, Surrealism, Modernism, Impressionism, Post-Impressionism and Cubism. Dozens of artists took as their subjects absinthe drinkers and the ritual paraphernalia: a glass, slotted spoon, sugar cubes – sugar softened the bitter bite of cheaper brands – and fountains dripping cold water to dilute the liquor.

Absinthe was, at its conception, not unlike other medicinal herbal preparations (vermouth, the German word for wormwood, among them). Its licorice flavor derived from fennel and anise. But this was an aperitif capable of creating blackouts, pass-outs, hallucinations and bizarre behavior, with nearly ten times the alcohol content of wine. Contemporary analysis indicates that the chemical thujone in wormwood was present in such minute quantities in properly distilled absinthe as to cause little psychoactive effect. It’s more likely that the damage was done by severe alcohol poisoning from drinking twelve to twenty shots a day. Still, the mystique remains.

Muse in a bottle

Rimbaud, Baudelaire, Paul Verlaine, Emile Zola, Alfred Jarry and Oscar Wilde were among scores of writers who were notorious absinthe drinkers. Jarry insisted on drinking his absinthe straight; Baudelaire also used laudanum and opium; Rimbaud combined it with hashish. They wrote of its addictive appeal and effect on the creative process, and set their work in an absinthe-saturated milieu.

In the poem Poison, from his 1857 volume The Flowers of Evil, Baudelaire ranked absinthe ahead of wine and opium: “None of which equals the poison welling up in your eyes that show me my poor soul reversed, my dreams throng to drink at those green distorting pools."

Rimbaud, who “saw poetry as alchemical, a way of changing reality” Edmund White notes in his biography of the poet, saw absinthe as an artistic tool. Rimbaud’s manifesto was unambiguous: he declared that a poet “makes himself a seer through a long, prodigious and rational disordering of all the senses.” Absinthe, with its hallucinogenic effects, could achieve just that.

Guy de Maupassant imbibed, as did characters in many of his short stories. His A Queer Night in Paris features a provincial notary who wangles an invitation to a party in the studio of an acclaimed painter. He drinks so much absinthe he tries to waltz with his chair and then falls to the ground. From that moment he forgets everything, and wakes up naked in a strange bed.

Contemporaries cited absinthe as shortening the lives of Baudelaire, Jarry and poets Verlaine and Alfred de Musset, among others. It may even have precipitated Vincent Van Gogh cutting off his ear. Blamed for causing psychosis, even murder, by 1915 absinthe was banned in France, Switzerland, the US and most of Europe.

Cultural hangover

The Green Fairy faded as a cultural influence for most of the 20th Century, to be replaced by cocktails, martinis and, in the 1960s, a panoply of mind-altering drugs. There were occasional echoes of its power, though mostly nostalgic.

Ernest Hemingway sipped the Green Fairy in Spain in the 1920s as a journalist, and later during the Spanish Civil War. His character Jake Barnes consoles himself with absinthe after Lady Brett runs off with the bullfighter in The Sun Also Rises. In For Whom the Bell Tolls, Robert Jordan brings along a canteen of the stuff. In Death in the Afternoon Hemingway explains he stopped bullfighting because he couldn’t do it happily “except after drinking three or four absinthes, which, while they inflamed my courage, slightly distorted my reflexes."

Hemingway even invented a Death in the Afternoon cocktail for a 1935 celebrity drinks book: “Pour one jigger absinthe into a Champagne glass. Add iced Champagne until it attains the proper opalescent milkiness. Drink three to five of these slowly."

In the late 20th Century, absinthe became a decadent reference point among a new generation of writers based in latter-day Bohemian outposts like San Francisco and New Orleans.

"The absinthe cauterized my throat with its flavor, part pepper, part licorice, part rot,” wrote precocious New Orleans horror writer Poppy Z Brite in a 1989 story, His Mouth Will Taste of Wormwood. The narrator and his boyfriend, jaded grave robbers, have found more than fifty bottles of the now-outlawed liquor, sealed up in a New Orleans family tomb. By the end, the narrator is fantasising about his first bitter kiss of the spirit from beyond the grave.

Still seeing green

Today’s absinthe is a “tongue-numbing drink” that “sharpens the senses,” says Lance Winters, master distiller and proprietor at St George Spirits, which offered the first legal absinthe in the US in late 2007.

“To my mind, absinthe imparts an air of the mystic, a touch of the supernatural – qualities I like in a drink now and again,” says Rosie Schaap, drinks columnist for The New York Times. She recommends “deploying the stuff with a light hand.” Her contemporary absinthe cocktails include the Fascinator – two parts gin, one part dry vermouth, two dashes of absinthe and one mint leaf.

In today’s literary circles, absinthe is more an amusement than a muse – showing up as a hipster cocktail at themed book-launch parties. Now widely available, in versions from the recently-made to the $10,000 a bottle vintage Pernod Fils, the drink seems just another popular culture reference, showing up in a Mad Men episode, as a Marilyn Manson-endorsed signature brand, Mansinthe, and inspiring innumerable drinks recipes, many of which use absinthe as a rinse, not a serious ingredient. You can even buy absinthe dilution apps for your smartphone.

Like the splash added to a cocktail, a literary reference to absinthe today adds a whiff of atmosphere, a reminder of the provocative and form-fracturing writers of the Belle Époque – and that a spirit can indeed inspire.

沒有留言:

張貼留言